April 15, 2021 | Campus

Commemorative stamp marks 100th anniversary of U of T’s discovery of insulin

By Geoffrey Vendeville

Canada Post unveiled the new stamp at an online symposium sponsored by Diabetes Action Canada, U of T’s Banting & Best Diabetes Centre and the department of medicine in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine

Among the treasures in the University of Toronto’s archives are letters from grateful diabetic patients and their families addressed to Frederick Banting (BMed 1916, MD 1922, Hon PhD 1923), who, along with Charles Best (BA 1921, MA 1922, MD 1925, Hon DSc 1947), J. J. R. Macleod and James Collip (BA 1912 TRIN, MA 1913), discovered the role of insulin in the disease.

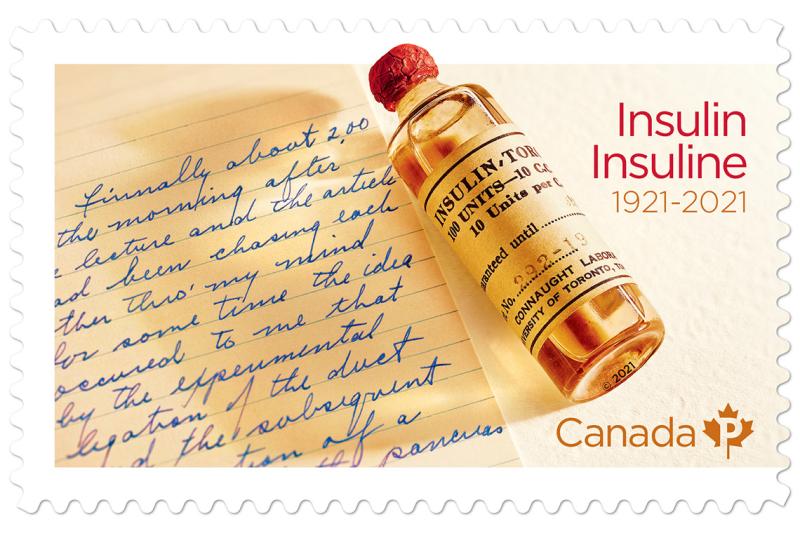

So, it’s fitting that this year’s celebrations marking the 100th anniversary of the medical breakthrough at U of T include a new Canada Post stamp.

The stamp, unveiled this week at a virtual celebration held by Diabetes Action Canada, U of T’s Banting & Best Diabetes Centre and the department of medicine, features an excerpt from Banting's unpublished memoir and an original insulin bottle with a red cap.

U of T researchers Scott Heximer and Patricia Brubaker worked with Canada Post and Banting House to ensure the stamp’s historical accuracy and help source archival material.

“When we got into this, we didn’t realize everything that went into making a stamp,” says Heximer, an associate professor and chair of the department of physiology in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

“When we got into this, we didn’t realize everything that went into making a stamp”

In addition to the stamp itself, the unveiling includes an official first day cover that also required fact-checking.

“It was fun,” says Heximer. “Our local committee was sitting around looking at pictures of Banting and letters addressed to the doctors in Toronto, and these were all things that went into building this official first day cover.”

One hundred years ago, Banting – a surgeon with a struggling practice in London, Ont. and little research experience – approached Macleod in U of T’s department of physiology in search of the support and equipment necessary to carry out his experiments. Macleod offered Best, who had recently graduated with a degree in physiology and biochemistry, the opportunity to work with Banting. Together with Collip, a biochemist on sabbatical from the University of Alberta, the researchers succeeded in producing a pancreatic extract from cattle that prevented death from diabetes.

Brubaker, a professor in the departments of physiology and medicine, notes that the influence of Banting, Best, Collip and Macleod can still be felt in the department of physiology. For example, she says, Best was chair of the department when Professor Emeritus Mladen Vranic (Hon DSc 2011) was hired.

Vranic, in turn, hired Brubaker, who won a lifetime achievement award from Diabetes Canada last year and whose research has contributed to the development of drug treatments for patients with type-2 diabetes. The drugs work by stimulating the secretion of insulin, helping to lower blood sugar levels and reduce appetite, among other effects.

The discovery was such a monumental achievement that a stadium full of people listened to Banting discuss the research

In 1923, Banting and Macleod were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Banting was the first Canadian to win a Nobel and remains the youngest winner of the prize in physiology or medicine (he was 32). Banting and Macleod shared the prize with Best and Collip.

The discovery of insulin was such a monumental achievement that a stadium full of people listened to Banting discuss the research, according to Brubaker.

“It was considered not a cure for diabetes, but a cure for death due to diabetes,” says Brubaker, who lives with type 1 diabetes herself and has devoted much of her career to understanding the disease. “Type 1 diabetes was a death sentence – a slow, prolonged, painful death – and it affected mostly children.”

The announcement of a lifesaving treatment was especially welcome news after the end of the First World War and a global pandemic that, like today’s, killed millions.

“This was an exciting ray of sunshine,” Brubaker says.

In March 1922, a Toronto Star bold-face headline proclaimed: “Toronto Doctors on Track of Diabetes Cure.”

Fan mail poured in for Banting and his colleagues

Soon, fan mail poured in for Banting and his colleagues.

Teddy Ryder, a five-year-old diabetic admitted to hospital weighing just 26 pounds, received his first insulin shots in January 1922. The next year, he wrote a letter to Banting in sprawling capital letters that filled the page. It said: “I wish you could come to see me. I am a fat boy now and I feel fine. I can climb a tree.”

Canada has issued stamps since 1851, though most early examples featured English royalty, according to Jim Phillips, director of stamp services at Canada Post. Since then, Leonard Cohen, Alexander Graham Bell and Viola Desmond are among those whose images have graced the tiny squares.

As for Banting, he was last featured on a Canada Post stamp in 2000.

“We see ourselves among the oldest Canadian storytellers,” Phillips said, adding that the discovery of insulin is a “fantastic story” for a stamp.

“These are real heroes, these four guys, and the University of Toronto for backing them and giving them space for their research ... This is a very, very positive story – and I think we need positive stories more than ever right now.”