May 11, 2017 | Alumni

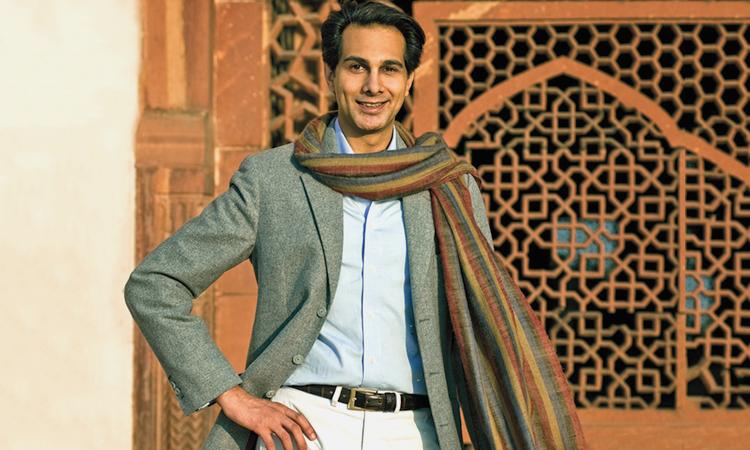

Interview with Amin Jaffer

An Indian Art Expert’s Journey from the World’s Leading Art & Design Museum to a Global Auction House

By Diana Kuprel

Dr. Amin Jaffer (BA History of Art) is the International Director of Asian Art at Christie’s in London, and specializes in Indian art in the age of European influence. After earning his PhD at the Royal College of Art in London, he spent 13 years as a curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum, where he authored Furniture from British India and Ceylon (2001), Luxury Goods from India (2002) and Made for Maharajas: a design diary of Princely India (2006). He was co-curator of the V&A’s blockbuster 2004 exhibition Encounters: the meeting of Asia and Europe, 1500-1800, which explored the artistic and cultural encounter between Europe and Asia following the discovery of a sea route to India by Vasco da Gama in 1498. He also co-curated Maharaja: the Splendour of India’s Royal Courts and co-edited the accompanying catalogue. He lectures frequently in Europe, America and India and contributes regularly to journals and major newspapers.

Arts & Science spoke with Jaffer at the Christie’s office about his journey from Africa to London, via Toronto, and what compelled him to become an expert on Indian art.

A&S: Your family traces its roots far back to Africa. How did you end up in Toronto?

AJ: It’s a long story. We were a merchant family trading between India and Africa. By the second half of the 19th century, the family was firmly based in Africa, on the coast in Zanzibar. By the 1870s and 1880s, they had come inland and my grandfather’s grandfather started trading, manufacturing and dealing. Then his son and his sons after—my uncles and my father—carried on in business.

The family on my mother’s side, which was largely a professional family, was based in Kenya. So I have a strong African background and identity. My parents and grandparents on my father’s side had no immediate link or relationship to India: culturally they spoke Indian languages and ate Indian food but they were not raised in India nor were their parents raised there. And because educational opportunities were limited in Africa, beyond a certain age, everyone had to be educated abroad.

While I was growing up, there was a lot of risk to businesses in Africa because of nationalization and political unrest. My father made some investments in North America. We bought a house and lived in Canada for a while. But ultimately Canada didn’t work out for him and he much preferred his life in Africa. When he got older, he went back to business in Africa. But the stay in Canada was long enough for my siblings and me to have exposure to North America and for my education to be based in the Canadian school system.

A&S: Given the family’s long ties to commerce, how did you become a curator?

AJ: I admit I was confused about a career path when I was a student at U of T. I started off in international relations, but quickly realized I didn’t enjoy the economics and political science introductory courses, which took place in huge auditoria. So I took a course on the history of French Baroque architecture, which I enjoyed thoroughly.

The real catalyst though was attending classes on decorative arts that were in an arrangement with the ROM. I took a couple of courses with Peter Kaellgren on the history of ceramics; he was a curator in the ROM’s European Department, who turned out to be hugely influential for me. I learned to understand the physical properties and style of works of art, and how to extrapolate from the physical design to read in broader messages of what these objects say about society and culture. I found the object-based work much more interesting than straightforward art history based on painting analysis. And I decided I loved being in a museum environment and that I should pursue the possibility of further museum-based studies. Kaellgren suggested I go to England’s Royal College of Art, which has a two-year master’s program in history of design, and where you work in the V&A and write your thesis on object or collection in that museum.

When I started to explore the V&A, I discovered an extraordinary 18th-century chair in the Indian gallery, completely English in design but made in ivory in India. That sparked an interest in the idea of hybridity and cultural fusion.

I ended up changing my master’s to a doctorate. After I completed it, the V&A gave me a job, which was to produce definitive catalogues of some of their collections. I also produced a major exhibition called Encounters: The Meeting of Asia and Europe, about east-west cultural exchange.

A&S: So how did your father feel about you studying art?

AJ: To tell you the truth, I didn’t tell him.

I’ve been quite a decided person in my life. I can’t do something unless my heart is really in it, and that goes from the minute to the grand things in life. When I was taking my undergraduate studies, for instance, I knew I couldn’t do the economics and political science courses—I couldn’t grasp their significance to my life—but now that I’m 50, I’ve become deeply fascinated by those subjects. What was significant to me at the time was good architecture, a beautiful object, works of art. I knew that I had no choice but to work in the world of culture, though at the time there was no guarantee that you would have future employment, because Canada was a tiny market and at the time the world was much less evolved in terms of building a career in the cultural space. What could one do with an art history degree? Of course my fantasy was to get a great job as a curator at a museum, but even that was like a pipe dream. But it happened.

A&S: What does it mean to be a curator?

AJ: When you’re a curator, you become involved in the interpretation of the past because of the works of art that you display, what you say about them in exhibitions and books—and you begin to influence what people think and how they learn about the past and other cultures. In a way, a curator is an educator and you can really change people’s lives by what you show them and how you show it to them. An exhibit can change one’s vision of a culture, place or artist. It is a big responsibility and can have a lasting effect. Still today, I have people come up to me and say, oh, I saw that exhibition and read your books and they totally changed my views and understanding. It’s immensely fulfilling.

A&S: You spent 12 years as a curator in the V&A. Are there any particular projects that stand out for you?

AJ: I’d have to say my exhibition Encounters, which was about looking at Asia from a Western perspective and looking at the West from an Asian perspective in the 16th and 17th centuries. I was showing Indian, Japanese and Chinese objects that depicted Europeans, showing how these artists caricatured Western features, behaviours and mannerisms. We didn’t expect it but the press went totally crazy because they recognized that by coming to this exhibition you could understand the encounter between Asia and the West. One of the art critics at the time wrote a beautiful line: this is an exhibition that removes screens from the mind.

A&S: Why did you make the move to Christie’s?

AJ: It was around the time I was writing a book on the Maharajas, in conjunction with a major exhibition, that I was started considering working for Christie’s. At that point, I had to take the alarming decision of leaving the academic art world for the commercial art world. It was a huge leap to go from a museum environment with its academic and philanthropic objectives into business. It took me six months to decide.

A&S: I guess your father’s influence came in in the end.

AJ: Yes, my foray into the commercial world saw my father’s genes kicking in. I admit I wanted to earn more than I was making as a civil servant, prove I could survive in the real world, ride the crest of the Asian economies that were rising, monetize my rolodex—all sorts of things that I could do by joining an auction house.

A&S: What is the most exciting thing about the work at an auction house?

AJ: It’s a completely different and exciting world. At Christie’s I’ve been involved in markets, sales, profiling works of art, publicity for artists and objects that I feel passionately about.

But the most exciting thing is when a client trusts you to advise on a work of art that they will then invest in or buy. I’ve been lucky to be involved in transactions in the $20 to 60 million dollar level. You become very close to your clients when you transact in that way. It’s a relationship that relies on good faith and trust and their high opinion of you ethically and of your aesthetic judgment. Helping a client build a collection is the most gratifying aspect of my work.

A&S: What is it that captivates you about Indian art?

AJ: I had a very classical upbringing: I was interested in Renaissance French and Italian art, in ancient Rome. India came to me later. India post-1400 Islamic invasions when the Europeans arrived was a period when there was a lot of trade between Asia and the West and you see the development of a syncretic system of belief, a system of architecture that combines different design influences and technologies. It’s anything and everything.

And myself being Indian ethnically but not being born or raised in India, I’ve always been interested in hybridity and mixture and cultural fusion. Pure works of art don’t hold fascination for me because they are born or made or used in one culture. I am interested in those that are produced in one culture for consumption in another, and consequently that are used and perceived in different ways.

So why is it that the panels of Japanese lacquer that arrived in Europe were so prized that they were mounted in royal furniture? Or why is it that Chinese porcelain objects that came to the West were richly mounted in gold and silver gilt mounts? Because they were exotic and strange and represented different worlds and technologies.

But it was also mundane things that were often prized and valued because when you take a mundane thing out of context it becomes a rare and special thing. Because I was always ethnically different wherever I was, because even in Africa we were a minority, I became fascinated by the idea of exoticism and difference and that really formed the basis of my academic career.

My book on the Maharajas is about luxury objects made in Europe for Indian princes during the period when they move out of their traditional palaces and start to build Western houses with dining rooms and billiard rooms. They go to London and Paris and start to shop for these homes. And they reset all their jewellery in Western style and start to drive cars and play tennis. There is this whole cultural shift which we’re still seeing today. Indians traditionally sat on textiles on the ground and the idea of sitting at tables is a Western intervention. I was interested in all these changes and how they happened and how critical objects and works of art were in this development. That’s become the backbone of my career.

A&S: Do you think you’ll ever go back to the museum world?

AJ: I’ve maintained links with the museum world and I’m lucky to work with a couple of collectors who are doing things on an institutional level: they buy works of art of museum quality to give or lend to museums.

I might go back after a few years, but I still have a far way to run. The market is very busy and I enjoy the activity.

And London is a great city for public art. I’ve sat on boards of museums and foundations and I enjoy being able to give something back to the public.

Read more interviews with alumni from the Faculty of Arts & Science.