February 12, 2019 | Alumni

The U of T alumna who saved her husband from a superbug

By Françoise Makanda

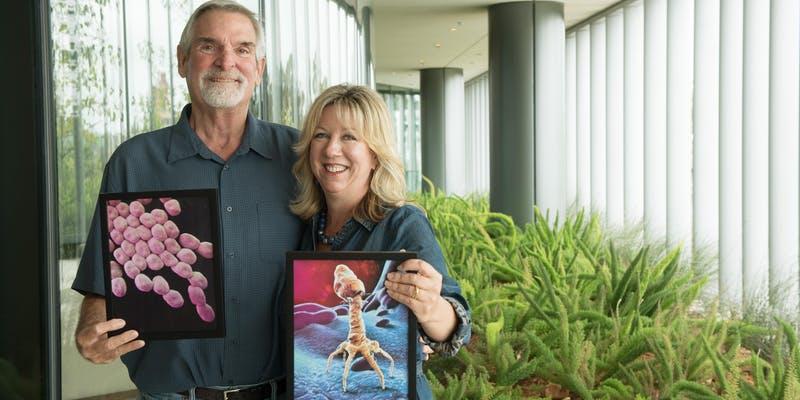

Tom Patterson and U of T alumna Steffanie Strathdee (BSc 1988 SMC, MSC 1990, PhD 1994): "How could a bacterium we considered wimpy be something that is taking my husband down, and we have no antibiotic left to kill it?”

University of Toronto alumna Steffanie Strathdee (BSc 1988 SMC, MSC 1990, PhD 1994) has a new book out. The Perfect Predator: A Scientist’s Race to Save Her Husband from a Deadly Superbug: A Memoir, recounts her husband’s fight against an antibiotic-resistant superbug.

After a trip to Egypt in November 2015, Strathdee’s husband Tom Patterson fell ill. The couple initially thought it was food poisoning, but Egyptian doctors diagnosed him with pancreatitis. When his symptoms worsened, he was flown to Frankfurt, where doctors discovered that he had an abdominal abscess from a gallstone obstruction that was infected with Acinetobacter baumannii, an antibiotic-resistant superbug that tops the World Health Organization’s list of the deadliest superbugs.

This bacterium, as Strathdee describes it, is good at stealing antibiotic-resistant genes and can live under extreme conditions. A few weeks later, he was sent from Frankfurt to a hospital at University of California San Diego, near where the couple currently resides. Her husband’s condition rapidly deteriorated as the superbug colonized his body. He went into septic shock and remained in a coma for two months.

“First, I was embarrassed because I’m an infectious disease epidemiologist. My husband was dying from a superbug infection, and it caught me off guard because this was bacteria that I used to plate on Petri dishes when I studied microbiology at U of T,” said Strathdee.

“I went from embarrassed to angry. How could a bacterium we considered wimpy be something that is taking my husband down, and we have no antibiotic left to kill it?"

Strathdee earned all of her degrees at U of T, including her PhD in epidemiology from the Dalla Lana School of Public Health in 1994, which was then known as the School of Community Health. She is currently an associate dean of global health sciences at the UC San Diego School of Medicine.

As her husband fought for his life, Strathdee did research on the internet and stumbled upon phage therapy, a treatment she had learned about during her undergraduate studies at U of T. Phage therapy stems from bacteriophages, which are viruses harvested from soil, dirty water and human waste that specifically prey on bacteria.

“When students are sitting in their classroom, eyes glazing over because it’s a boring lecture, just remember that a little piece of information can come back later and help you save somebody’s life. That’s what happened in our case,” said Strathdee.

Read about Steffanie Strathdee as one of Time magazine's 50 people transforming health care

French Canadian scientist Félix D’Herelle discovered bacteriophages in 1917 and first used phage therapy to successfully treat humans in 1919. Phage therapy lost its popularity in the 1940s following the introduction of penicillin, but was taken up by the Soviet Union. Western experts shunned away from it – until now.

Strathdee emailed phage researchers all over the country, and discovered two teams at The Center for Phage Technology at Texas A&M University and the U.S. Navy Medical Research Center that agreed to help. Both teams identified several phages that were active against Patterson’s bacterial isolate, and purified them in time for the medical team at UC San Diego to administer them to Patterson.

Since phage therapy remains experimental in North America and Western Europe, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted permission for it to be used to treat Patterson on a compassionate basis. It was a huge gamble, but it paid off. Three days after beginning intravenous phage therapy, Patterson woke up from a deep coma and began to recover.

“My training in epidemiology helped me a lot. It helped me dissect the problem I was facing and then conduct research to seek potential avenues to treat Tom. But it took a global village to achieve our miracle,” said Strathdee.

“I dream of one day taking phage therapy to lower- and middle-income countries that bear the biggest burden of superbug infections and don’t have access to the resources that I did.”

Phage therapy is now considered as a potential treatment for the superbug crisis in North America, following the publicity the case received. In light of their success, Strathdee and colleagues have opened the first phage therapy centre in North America at UC San Diego, called the Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics. They have successfully treated several other patients suffering from superbug infections in the U.S. and abroad, and will launch two clinical trials of phage therapy in 2019.

Patterson and Strathdee shared their experience in their book, which she hopes will help others understand the growing threat of superbugs and the potential cure on the horizon.

Patterson and Strathdee will be sharing their story at Dalla Lana on March 26 at noon in the seventh floor lounge in the Health Sciences Building.