May 27, 2024 | Alumni

Alum Christina Wong thrust into spotlight after making Canada Reads shortlist

By Adam Elliott Segal

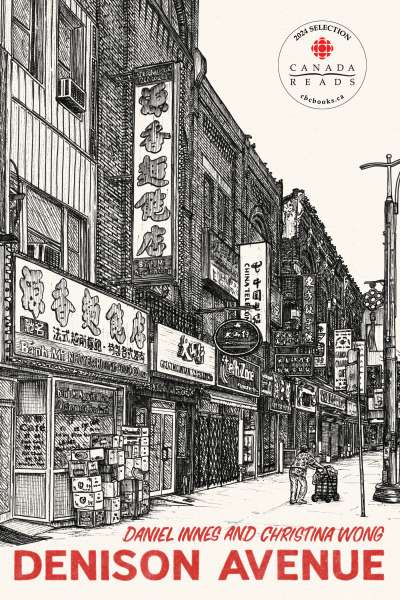

Author and U of T alum Christina Wong. Photo courtesy of Daniel Innes.

When Christina Wong (BA 2003) began writing Denison Avenue six years ago, she couldn’t have imagined the journey it would take her on.

“If you asked me a year ago if this would happen, I honestly wouldn’t have believed you,” says Wong, who earned her bachelor’s degree in environment and society in 2003 as a member of St. Michael’s College.

Denison Avenue was included in this year’s Canada Reads, CBC’s literary contest that pits book against book in a winner take-all battle royale. It’s a sales boon for authors and publishers, thanks to the national attention.

Each writer is paired with a celebrity champion, in Wong’s case former Calgary mayor Naheed Nenshi. The televised debate, now in its 23rd year, launches participants into another literary stratosphere; so it’s still sinking in that Wong’s book, published by indie darling ECW Press, is now reaching so many Canadians across the country.

A very Toronto book

Denison Avenue is Wong’s debut novel, co-written with illustrator Daniel Innes. The two collaborated from conception, envisioning an illustrated, two-sided book that defied conventional categorization as a graphic novel. It took her five years to write, from original idea to book deal to working for more than a year with her editor, Jen Sookfong Lee.

It is a very Toronto book; a very U of T book in many ways.

Her time spent at St. Michael’s College surrounded by likeminded students, many of whom she is still friends with today, was critical in her artistic journey. Wong was active then in student council, the drama program (her minor, along with East Asian Studies) and played touch football.

“U of T had a very nurturing environment. It pushed you as a person and a student. My degree allowed me to think outside my discipline, which was foundational for me, and allowed me to approach things from an interdisciplinary viewpoint. If it weren’t for those courses, teachers and instructors, I don’t think I would have reached the next level in my career. It set a foundation for me to pursue my graduate studies and I’m forever grateful.”

Readers will recognize neighbourhoods and streets and laneways that surround the university campus.

“One or two spots show up in the book. As a student, I didn’t even realize there were ginkgo trees near campus. I’ve always known them to be beautiful, but I only noticed them after I graduated,” she says.

That sense of intimacy, through language, geography and space, is everywhere in her book, and that unique understanding began back in Wong’s undergrad. She remembers her student days fondly: holed up in Hart House studying, hanging out at Future Bakery or the Green Room on Bloor Street and the Poor Alex Theatre on Brunswick Avenue, or frequenting the inexpensive Chinese bakeries along Spadina Avenue.

Writing a rarely seen protagonist

The novel follows the protagonist, Cho Sum, after the loss of her husband. She walks the streets in and around Chinatown and Kensington Market, collecting cans for income and meeting people of all ages and backgrounds along the way. Above all, it’s a story of an elderly immigrant woman navigating loss, a rarely seen protagonist in Canadian literature.

Wong, who is also a playwright and audio storyteller, uses two languages, English and Toisan, a regional dialect from the port cities of Guangdong province that arrived in North America with the first Chinese immigrants. It’s distinct from its lingual cousin, Cantonese, and Wong grew up with both dialects at home.

By writing the novel in two languages that live side-by-side on the page, and in first person rather than third, Wong gives the reader a visceral sense of immediacy into an elderly immigrant’s relationship to a city where English is not her first language, employing creative punctuation to create dissonance. Scraps of paper reveal names of streets and landmarks Cho Sum recalls, and Innes’ illustrations of Toronto landmarks (local cafes, Honest Ed’s) are like windows into time – some buildings have already been torn down to make way for condos.

Relying on lived family experience

Wong relied on her own family’s experience going to doctor’s appointments and hospital visits to create Cho Sum’s world.

“What we hear as an English speaker is going to be very different from someone for whom English is a second language. I see it reflected in how my mom interprets things, and how I interpret things. I wanted to show the struggles of language, even if you’ve been here for a long time,” says Wong. Documenting Toisan, and the way Wong formatted the book, was all very intentional, she says.

“It was the language of Chinatowns across North America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. I wanted you to see the world through the eyes of an elderly Chinese senior.”

Her advice for future writers is simple. “Make sure you stay true to who you are and what you want to say. Find your voice. I know it sounds cliche, but just keep going because everyone has a story to tell and only you can be the person to tell it.”

Originally published by University of Toronto Faculty of Arts & Science