August 23, 2022 | Alumni

“A gripping story about terrible wrongs”: Valley of the Birdtail draws lessons for Canada

By Nina Haikara

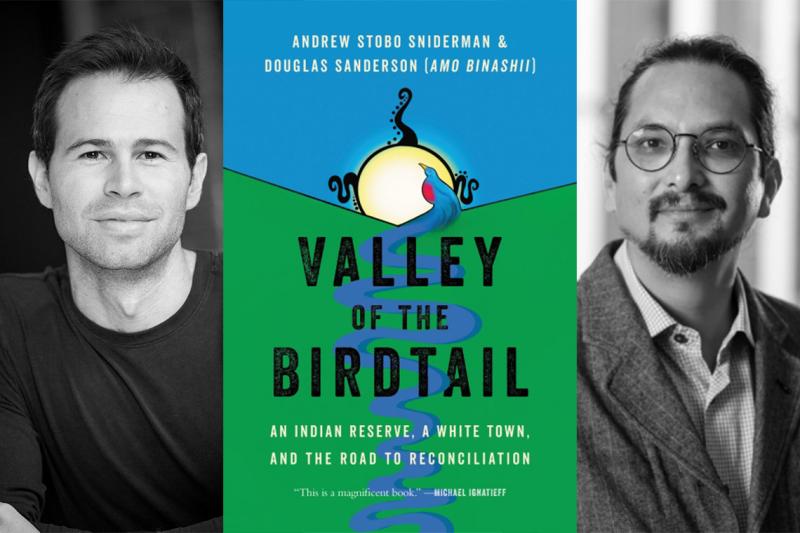

In Valley of the Birdtail, alumni Andrew Stobo Sniderman and Douglas Sanderson tell the story of two communities in Manitoba “divided by a valley, a river and 150 years of racism” (photos by Natasha Launi and Dewey Chang)

The Waywayseecappo Indian reserve was created on the West side of the Birdtail river in western Manitoba in 1877. Two years later, on the other side of the river, white settlers established a town named Rossburn.

The story of these two communities is captured in Valley of the Birdtail: An Indian Reserve, a White Town, and the Road to Reconciliation (HarperCollins 2022).

Co-authors Andrew Stobo Sniderman (JD 2014) and Douglas Sanderson (Amo Binashii) (JD 2003) write that the two communities are “divided by a valley, a river and 150 years of racism.”

“We have tried to tell a gripping story about terrible wrongs,” says Sniderman, a graduate of the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Law. “And I think you learn something essential about Canada.”

In addition to being a lawyer, Sniderman is an award-winning freelance journalist. His reporting and opinions have appeared in the New York Times, the Globe and Mail, Maclean’s magazine, the Toronto Star, and the Montreal Gazette. In 2011, his feature on Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission on residential schools won the Canadian Association of Journalists (CAJ) award for best print feature.

Sanderson, meanwhile, is an associate professor in U of T’s Faculty of Law, the Prichard Wilson Chair in Law & Public Policy and decanal adviser on Indigenous issues. “What my work has been trying to do over the years is to think about how Indigenous and settler people can live side by side in a condition of equality,” Sanderson says.

They had found a way, amazingly, to equalize the funding

The book’s origins can be traced back to Sniderman’s early law school years. After his first year of study, he worked as a reporter for Maclean's magazine and came across Waywayseecappo and Rossburn.

“These communities were interesting because they had schools nearly side by side – one on reserve, one in town – and they had found a way, amazingly, to equalize the funding between these schools,” he says.

He wrote an article for Maclean’s, but the story of these two communities continued to weigh on his mind, even after law school.

“I had a feeling that there was more to this story,” he says. “I kept thinking about it. I was haunted by it. In 2017, I quit my job in Ottawa and booked a flight to Manitoba.”

During that first month-long trip, Sniderman met the people who would become the main characters of the book.

“The biggest challenge was earning the trust of people in both communities,” says Sniderman, who spent five years conducting interviews and reviewing archival material.

“That trust was earned, over time, by showing I was there to really listen, put in the work and take the time necessary to do a good job.”

I see this book as a great way to mesh together big ideas with lived experience, to show a way forward

When he began researching the book, Sniderman says he realized he could not do justice to the story working alone. He thought of Sanderson, who had taught his small-group, property law class. After graduating, Sniderman had kept in touch with his former professor and read his latest publications.

“Douglas had a macro sense that I just didn't have,” says Sniderman. “I thought: maybe the two of us can put all the pieces together? And in order to really grapple with the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in this country, it seemed vital for the two of us to do the work of combining our perspectives.”

Sanderson, for his part, says co-authoring a book with his former student was a great experience.

“We're at a place now where people are talking a lot about reconciliation, opportunities for change,” he says. “But the ideas are really complicated. It's hard to explain how to set out a different vision of public policy for the future. I see this book as a great way to mesh together big ideas with lived experience, to show a way forward.

“People will learn new things, relevant today. For example, since the war began in Ukraine, we hear Canada is home to over one million Ukrainian-Canadians. In our book, we tell the story of why that happened, and how that happened – and how we made it happen, which is a missing piece of the context for the way in which we look at each other today.”

I think you learn something essential about Canada

As a non-Indigenous law student, Sniderman says he has long sought to understand why schools on reserves were receiving so much less government funding.

“I just couldn't make any sense of [unequal funding]. I kept looking for a way to understand this problem and to try to explain it to people,” says Sniderman, who plans to pursue doctoral studies at Harvard Law School. His master’s research examined the relationship between Brown v Board of Education, the case that desegregated Black students in U.S. schools, and the integration of Indigenous students in Canada.

Both authors say the book attempts to show how different treatment by the government created and entrenched inequalities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. “There is nothing accidental or inevitable about the way things are,” Sniderman says.

“We offer a bold vision, not suggestions for a new program here or increased funding there,” Sanderson adds. “We want to start a real conversation about an equitable and shared future.”