April 23, 2018 | Campus

U of T library acquires the oldest English-language book in Canada

By Romi Levine

(All photos by Romi Levine.)

As people around the world show their appreciation for the printed word on United Nations' World Book Day, University of Toronto's Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library is making history with the acquisition of what is thought to be the oldest English-language book in Canada.

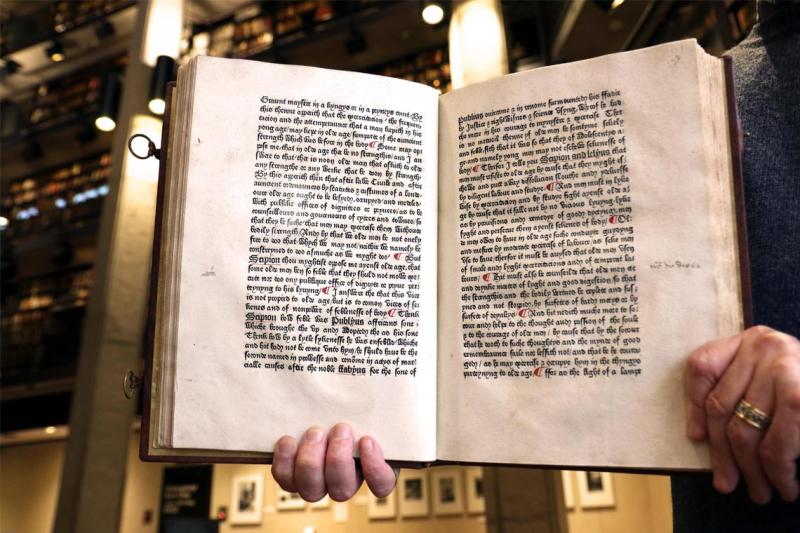

Printed in 1481, the book includes three texts – Cicero’s De Amicitia (treatise on friendship), De Senectute (treatise on old age) and Giovane Buonaccorso da Montemagno’s De Nobilitate (treatise on nobility).

The book, referred to as the Caxton Cicero, also marks a special milestone for U of T Libraries: it’s the library system’s 15 millionth item.

Only 13 copies of this book exist in its complete form, says Pearce Carefoote, the interim head of rare books and manuscripts at Fisher Library, and he says it’s a rarity in many ways.

“This is the very first text by any classical and humanist author that has been translated into English,” says Carefoote.

The book was one of about 108 books printed by William Caxton, a merchant who is credited with bringing the printing press to England in 1476.

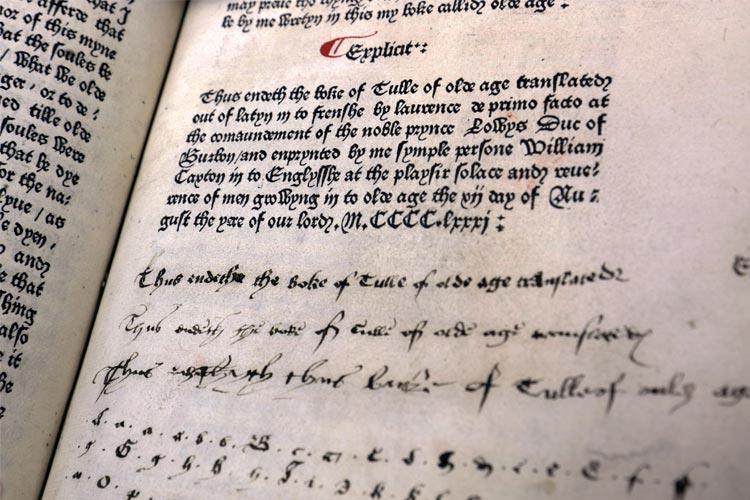

At the end of the first text, Caxton includes a colophon (pictured below), which is an imprint by the printer that includes information about the book’s publication.

Through clues buried inside the book, one can trace the history of the Caxton Cicero back to one of its first owners, Thomas Shupton – thought to be a monk during the time of Henry VIII. It was then given to 16th-century politician Sir Robert Coke, who passed it on to his nephew. After his nephew’s death, the book was given to Sion College in London, which kept it until 1977 when it was bought by Mexican author Roberto Salinas Price through a rare book dealer.

U of T acquired the text from Price's estate, which was made possible by many donors, led by the B.H. Breslauer Foundation and with the support from the University of Toronto through a matching grant.

Up until this point, the oldest English-language book in the Fisher Library's collection was its 1507 copy of The Golden Legend, which it acquired in 2016.

The Caxton Cicero allows Fisher to tell a complete history of English-language printed materials, says Carefoote.

“We had this great run of English printed materials from 1507 right up to 2018,” he says. “The one thing we were missing was an English incunable (books printed before 1501).”

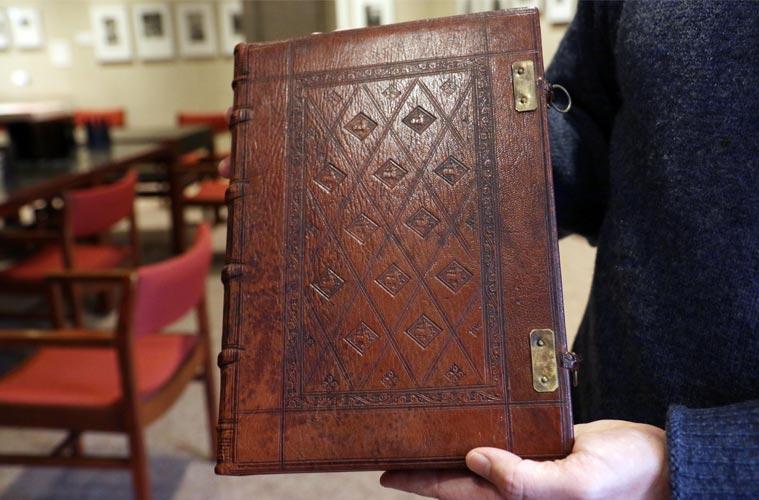

Though the book is over 500 years old, the binding was made in the 1980s by a craft binder in Britain, created in a style that was sympathetic to the 15th-century aesthetic, says Carefoote. It was created using a technique called blind tooling, using leather darkened by carbon.

You could think of the paper used to print the Caxton Cicero as an early example of recycling.

“Paper at this period is made out of linen – often linen undergarments that are reconstituted as paper,” says Carefoote.

The type is essentially a fingerprint, unique to Caxton, says Carefoote.

“One of the ways you can identify books (in early printing) is by type,” he says. “Each printer is making his own type out of lead.”

Carefoote envisions the book being of great interest to a wide range of scholars at U of T and beyond, from those studying book history who can look at the paper, the ink and the type to the departments of classics, medieval studies and history.

Soon, the book will also be digitized, so researchers all over the world will have access to this historical artifact.