May 15, 2023 | Alumni | Career Support

Neurologist Suvendrini Lena on her unique path to playwriting

By Tabassum Siddiqui

Suvendrini Lena, an assistant professor in U of T's Temerty Faculty of Medicine, bridges the gap between medicine and theatre in her work as a playwright. Photo courtesy of Suvendrini Lena.

Suvendrini Lena (BA 1995 TRIN, PGMT 2011) has a foot in two worlds: she’s a staff neurologist at Women’s College Hospital and an assistant professor of neurology and psychiatry in the University of Toronto’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine – and a successful playwright.

After earning a B.A. in history and political science as an undergraduate student at Trinity College, Lena went on to a graduate degree in neurology at U of T – all while exploring her longstanding interest in theatre and writing.

But the path to writing her first play was a bit of a surprise – certainly to her neurology professors. Instead of presenting a final research project, she wrote a piece of theatre – The Enchanted Loom – that explored the experience of a patient with epilepsy. It was later produced by Toronto’s Cahoots Theatre and published as a book.

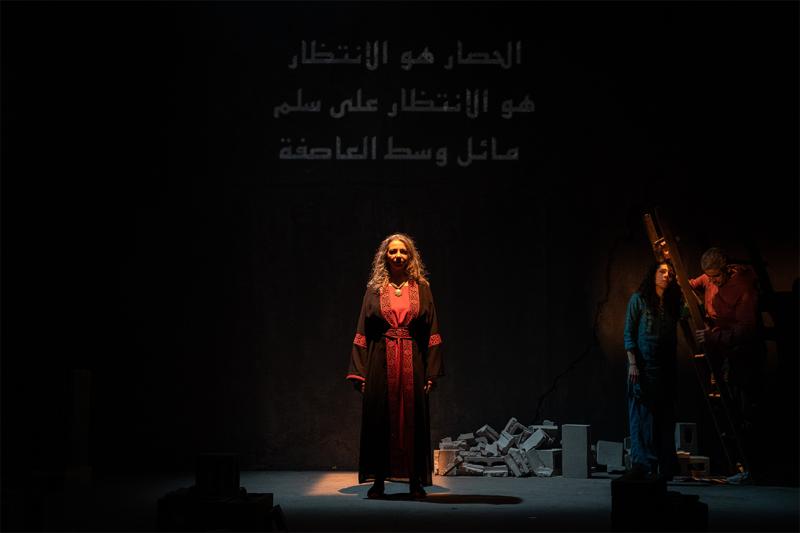

Since then, Lena has continued to work in both medicine and theatre – her latest play, Rubble, was performed at Theatre Passe Muraille this spring. A dramatic imagining of the works of Palestinian poets Mahmoud Darwish and Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, the play was inspired by Lena’s work in Gaza in 2002 while still a medical student. Years later, Tuffaha’s poetry reminded her of the struggles – and the rubble – she witnessed while there.

We asked Lena to share how her university experience informed her path to bridging the gap between medicine and the arts.

how did you find your way from medicine to theatre?

I always wanted to be a writer. In the neurology program at U of T, you have to do a big research project in your last year of the program, but I realized my heart wasn’t really in research. I’m definitely interested in understanding things well and the arts are another way to do that – you get to interrogate something, but from a creative perspective. I ended up writing a play about a Sri Lankan patient with a complex case of epilepsy and all the difficult choices facing him and his family as a result of his illness. So that became the centre of my first play.

What was your professors’ reaction when you asked to submit a play as your final project instead of a research paper?

There’s an art to pitching – it’s about taking an idea that has legs and having people understand and feel invested. So, I think I did that convincingly and I had open-minded supervisors – I was very lucky that way. I had great support and supervision, and we presented a reading from that play at the research presentation at the end of the year. The audience gave it a standing ovation. I think there was something compelling for them because they could see themselves depicted in a very human way. Doctors are so often portrayed in a one-dimensional way in TV and film, so I try not to do that myself.

What inspired you to write Rubble?

I’m a lover of poetry – especially these two particular poets; their lyrical poems exist on many levels. You have to hear it out loud to be able to appreciate the meaning – the poems also give you a window into the humanity of people who might feel distant from you, but you can see that’s not the case. I felt like it was a doorway to explore and give voice to the Palestinian experience – in the last 60 years, they have been displaced and under occupation, and there’s been very little clarity about that historical experience; very few places for them to really tell their story. So, the play is trying to create that space as well.

were there any U of T mentors or faculty who made an impact on your educational and career path?

In my neurology program, Marika Hohol [Unity Health] and Richard Wennberg [University Health Network] were people I learned a lot from and who supported me. And during my undergrad years, I took courses in English and modern drama, including with an amazing professor, Alexander Leggatt – that’s really where my love of theatre was nurtured. He opened up the world of drama to many, many people. He was interested in ethics, philosophy and poetry – and really made it all accessible to us.

How did your time at U of T help shape the work you do today?

I first studied history and political science, but got heavily into theatre when I directed plays with the Trinity College Dramatic Society. Afterwards, I swore I would never direct anything again – everything was so complicated! But I got to understand that when you study a text as a director, it’s a completely different experience than reading it in class, right? You step into building a theatrical world – which is what playwriting and theatre-making is all about.

How does your work as a doctor intersect with your work as a playwright?

In medicine, we deal with a lot of very difficult things all the time – and there's a bit of trauma in there. If you empathize with your patients, then you can’t help but witness suffering. These are very moving things and you’ve got to stay open and alive to all that. I need an outlet – writing provides me with that outlet and theatre is special because you can explore human issues and relationships in a unique way. All kinds of writing can touch on that, but when something is written for the theatre and embodied by an actor, it gives an added dimension of reality.

What’s your approach to teaching?

I mostly do small-group teaching in the medical school curriculum and a seminar on medicine and the humanities. This semester, we’re doing a staging where we explore medical experiences and how physicians examine their own subjectivity. We also try to engage with issues of contemporary relevance, including issues of voice and representation in medicine and society.