June 29, 2022 | Alumni

Award-winning poet Liz Howard braids Western physics and Anishinaabe sky knowledge

By Kieran Kalls Rice

(Photo by Ralph Kolewe)

Consciousness, trauma, and survival explored through poetics. U of T alum and award-winning poet Liz Howard (BSc 2007 NEW) writes by braiding Western cosmology and physics with Anishinaabe sky knowledge and personal experience.

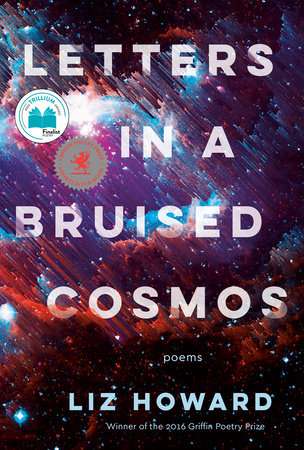

Her debut collection, Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent, won the 2016 Griffin Poetry Prize, was shortlisted for the 2015 Governor General’s Award for poetry, and was named a Globe and Mail top 100 book. A National Magazine Award finalist, her recent work has appeared in Canadian Literature, Literary Review of Canada, Room magazine, and Best Canadian Poetry 2021. Her second collection, Letters in a Bruised Cosmos, was published by McClelland & Stewart in June 2021.

Howard received an Honours Bachelor of Science with High Distinction from the University of Toronto in 2007 and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Guelph. She is of mixed settler and Anishinaabe heritage. Born and raised on Treaty 9 territory in Northern Ontario, she currently lives in Toronto and is an adjunct professor and instructor in the Department of English at U of T.

Howard kindly agreed to discuss her latest collection of poetry for Indigenous history month.

1. Before we jump into your writing, can you talk a bit about the work you’re doing at U of T?

This past year I had the honour of teaching poetry writing courses through the School of Continuing Studies, mentoring a graduate student in the MA in English in the Field of Creative Writing program, and teaching a third-year creative writing poetry class at the Mississauga campus. This coming year I will be serving as the Shaftesbury Creative Writer-in-Residence at Victoria College, which will involve delivering a keynote address in the fall and teaching a seminar on creative citizenship in the winter term.

2. You did your undergrad at U of T in psychology before completing your MFA in creative writing. That’s quite a departure. Can you talk about the transition from psychology to creative writing?

I have always been interested in the human mind, in its biological basis and the phenomenology of consciousness, cognition, and subject experience that arises from it. Such an interest, I think, lends itself to both the study of psychology and creative expression.

Coming from a family heavily impacted by mental health issues, and being the first in my family to pursue post-secondary studies, I felt a sense of urgency in studying psychology towards eventually being of help in some way, as a clinician or researcher. After graduating I was hired as a lab manager for an aging and cognition laboratory and gratefully had the opportunity to learn about the research process firsthand. I planned to go to graduate school in psychology and was working to pay down my student debt to allow for that possibility.

I decided what I wanted, needed really, to do was to write a book

At the same time, I was reconnecting with my love of poetry and writing by taking poetry classes and attending readings around the city. I found an incredible community of writers, thinkers, and art-makers. I decided what I wanted, needed really, to do was to write a book and I applied to a master’s program to facilitate that process.

3. Reading Letters in a Bruised Cosmos, I found myself looking up the definitions of scientific terms countless times. Is it fair to say that your background and training in science inform your poetry?

Absolutely. My background in science has informed how I interpret the world, my own thinking, and by extension, what I write. I find the beauty of neuroanatomical terms, like frontal pole, corpus callosum, or the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, compelling. I am also interested in the language and frameworks of other disciplines such as cosmology, physics, medicine, archaeology, and even environmental science.

In my latest book I braided aspects of Western cosmology and physics with Anishinaabe sky knowledge and personal experience to examine consciousness, trauma, and survival. For example, in one poem I reference astrocytes, which are star-shaped cells present in the human brain and spinal cord. I think the name has interesting connotations in terms of human pattern-recognition and analogical/metaphorical thinking. It also has resonances with Carl Sagan’s offering that “we are made of star stuff” and the Anishinaabe belief that humanity has its origin in the stars. So here is a cell that is part of the biophysical apparatus that facilitates or creates consciousness, that is composed, as all things are, of material forged in the bellies of stars, and itself resembles such a celestial body, at least as seen from the human vantage point of earth.

It’s hard not to reach for the poetic when one spends a bit of time thinking through this kind of inter-connectedness!

4. When were the poems of Letters in a Bruised Cosmos written? Was it done in an extended period of your life or was it condensed?

I wrote them between 2015 and 2020. The poem titled “Letter from Halifax” began as a letter written to a friend during January 2015 when my birth father passed away. There are a couple of poems in the book that were written in the week before the final manuscript was submitted. A lot of material didn’t make it into the book. I was interested in working rigorously with compression and the length of the book is reflective of that.

Each day I wake and rewrite

this and in doing so

destroy my memory

5. In the notes of Letters in a Bruised Cosmos, you credit Jacques Roubaud talking about his creative process as the influence for this passage: “Each day I wake and rewrite/ this and in doing so/ destroy my memory.” It made me curious about your own process. Are you someone who constantly revises their work? In terms of time management, how do you balance instinctual free-flowing writing with going back to edit work?

I constantly revise. I have edits that I’ve written into reading copies of my books. My practice tends to favour a lot of free-writing to generate material. I then set to work shaping that material, breaking it down, and then expanding upon it. Substantial editing seems to only come in close to the end once I’ve determined what the overall structure of the book will be.

6. How did your relationship with Dionne Brand form?

She was the poetry instructor at the University of Guelph in the creative writing master’s program, and I was fortunate to take two workshops with her. When she was appointed to the poetry editorial board at McClelland & Stewart she asked to see a manuscript based on the material I had composed during her classes. Amazingly, she was in support of it, and it was approved for acceptance by the full editorial board. I was also fortunate to have Dionne as my editor for this last book.

In general, my writing practice is informed by the concept of “two-eyed seeing” in which both Indigenous and Western perspectives are represented. I hope that my work speaks to all people.

7. As a poet, are you conscious at all of how accessible your work is to readers? In other words, does the reader influence how you write, or do you see writing poetry as a solitary meditation that one does for themselves?

My view of poetry is that all of it is accessible and that any reader’s experience or interpretation of a poem is valid. I came to an understanding though that not everyone views poetry this way and many readers turn to poetry for recognition and reflection and desire a firm scaffolding or point-of-access to do so.

In my second book I experimented with direct address and narrative as a way to speak directly to readers about my own lived experiences as opposed to my first book where I was more interested in the materiality of language.

8. Leanne Betasamosake Simpson refers to what she calls “coded disruption” as an artistic practice to speak to multiple audiences and “disrupt the noise of colonialism”. Would you say that you’re cognizant, as a writer, of how what you’re creating will be interpreted by Indigenous versus non-Indigenous audiences?

In my latest book I elected to use Anishinaabemowin without the aid of a direct English translation, as I had done in my first book. This was a way of speaking directly to language speakers but also to English-speakers as any word’s translation could be deduced from context.

In general, my writing practice is informed by the concept of “two-eyed seeing” in which both Indigenous and Western perspectives are represented. I hope that my work speaks to all people, and that any person could find recognition, inquiry, or inspiration from what I have written.

About the author: Kieran Kalls Rice is a writer of Coast Salish and Scottish-Canadian descent who is currently an undergraduate student at the University of Toronto’s Indigenous Studies and English programs.