February 6, 2020 | Alumni

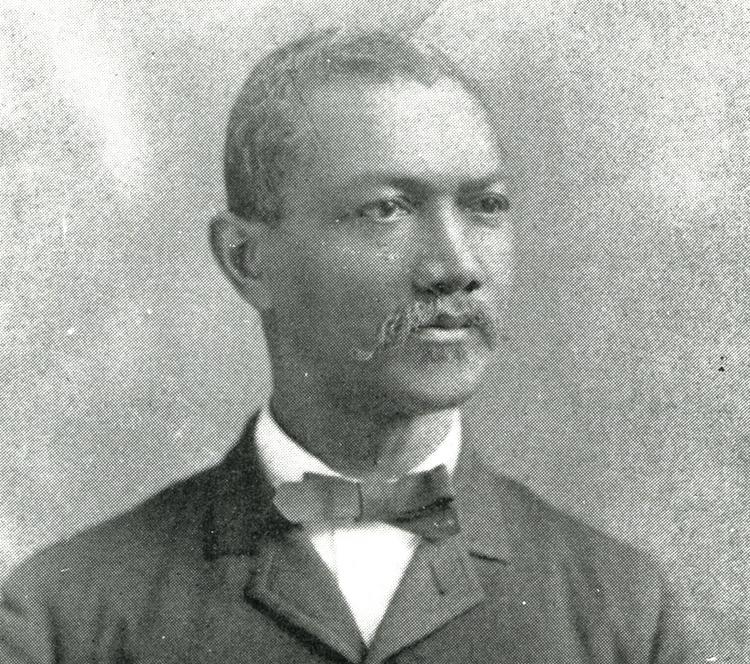

Doctor of courage: Alexander Augusta, one of U of T's first Black medical students

Rejected by American universities, Alexander Augusta completed his medical degree at Trinity Medical College then used his skills to fight for civil rights in his homeland

By Alice Taylor

Almost a century before Rosa Parks defied Alabama’s racial segregation laws, Trinity graduate Dr. Alexander Thomas Augusta refused to give up his seat in the “whites only” section of a Washington DC streetcar. Dressed in his U.S. Army officer’s uniform, Augusta was physically ejected from the streetcar. He railed against this injustice in letters to newspapers and government officials. In 1865, a year after the incident, Congress decreed that all streetcars in the nation’s capital were to be desegregated.

This was neither the first nor last time Augusta would challenge the discriminatory practices of his native country. Denied entrance to American medical schools on the basis of colour, he was granted admission to Trinity Medical College in the early 1850s, becoming the first Black medical student in Canada West.

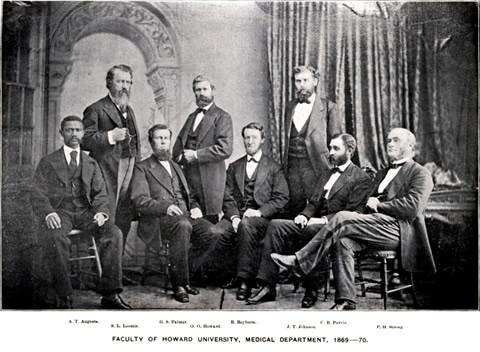

Augusta excelled at Trinity, so much so that U of T president John McCaul publicly acknowledged his superior intellect. Augusta took particular interest in anatomy, taught by Dr. Norman Bethune (namesake and grandfather of the more famous Dr. Bethune ). Augusta would later go on to teach anatomy for almost a decade at Howard University in Washington, as the first Black professor of medicine in the United States.

During and after graduating with an Bachelor of Medicine degree in 1860, Augusta worked for several years as a physician in Toronto, where he became a leader in the Black community. He offered medical care to the poor, founded a literacy society that donated books and school supplies to Black children and was active in antislavery circles on both sides of the border.

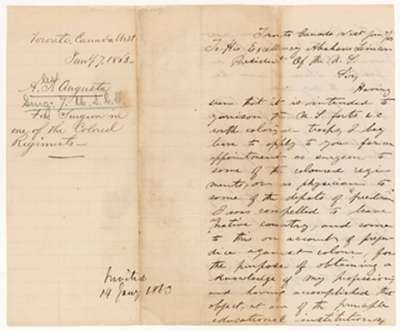

Despite his success in Canada, with war raging south of the border, Augusta felt duty bound to use his medical training in support of “my race.” On Jan. 7, 1863, less than a week after the Emancipation Proclamation authorized Black men to serve, Augusta wrote to President Lincoln requesting to be appointed as a physician to the newly created “colored regiments” in the Union Army. (In an odd twist of fate, two years later, Augusta would lead a procession of 75,000 “colored troops” through the streets of Baltimore as President Lincoln’s body passed though the city.)

In April, 1863 Augusta became the first African-American commissioned as a medical officer in the U.S. Army (at the rank of major) and one of only 13 to serve as surgeons during the war. Within two years, Augusta was promoted to lieutenant colonel and became the highest-ranking Black officer in the U.S. military.

Augusta mustered out of service in 1866, and for the next quarter century he remained active in the Washington DC medical community, variously working in local hospitals, private practice and as a university professor.

Despite his many accomplishments, however, Augusta and other Black doctors were refused admission to the local society of physicians. Unsurprisingly, Augusta fought back—all the way to Congress—but never gained entry into the DC medical society. On January 15, 1870, Augusta co-founded the National Medical Society of the District of Columbia, which accepted Black and white members.

Augusta also crusaded to desegregate DC’s regional transit system. When brutally attacked by white passengers—who objected to a Black man in an officer’s uniform—on a Baltimore train, Augusta again took his story to the press. In a letter published in multiple newspapers, he asserted his right as a Union officer “to wear the insignia of my office, and if I am either afraid or ashamed to wear them, anywhere, I am not fit to hold my commission.”

Several years later, Augusta testified before a Congressional Committee on behalf of his patient Kate Brown, who was seriously injured when she was forcibly ejected from the “white people’s car” on a train bound for Washington. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court; the 1873 Railroad Company v. Brown decision ruled that white and Black passengers must be treated with equality in the use of the railroad’s cars.

Dr. Alexander T. Augusta died at home four days before Christmas, 1890. Even in death Augusta broke the colour barrier. Interred with full military honours, he became the first Black officer buried at Arlington National Cemetery.