April 22, 2022 | Alumni

Earth Day: U of T alumni discuss the thrilling potential of their discipline: landcape architecture

Left to right: U of T alumni Doris Chee, Eha Naylor and Shelley Long have all worked on game-changing climate-related landscape projects.

More than ever today, landscape architecture and design have become key aspects of planning and building, which can no longer afford to ignore the natural world. This wasn’t always the case. For Earth Day, three University of Toronto graduates with diverse experience in the field convened to take stock of how far the discipline has come – and how far it can go.

Unabashed ecology advocates Doris Chee (BLArch 1984), Eha Naylor (BLArch 1980) and Shelley Long (MLArch 2015) share their thoughts on the changing perceptions and approaches of their profession, how landscape architects can lead the way in addressing issues like climate change, and some of the game-changing projects they themselves have worked on.

This interview has been condensed. Read the complete discussion at the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design.

Tell us a little bit about yourselves.

Doris Chee: I worked at various private and public offices for most of my career, until I landed at Hydro One, which is where I have been for the last 14 years.

I was always passionate about landscape architecture. I volunteered with the Ontario Association of Landscape Architects (OALA) newsletter when I became a member, helped mentor junior landscape architects, and represented the association at various meetings and committees. I’m still doing that. I worked my way up, so to speak, to the position of OALA president from 2016 to 2018. I also became involved with the Governing Council of the University of Toronto.

Eha Naylor: I chose landscape architecture because it was a field where I could combine art and science – I had an interest and natural affinity for both, particularly natural science. It was really exciting when I found a program and a profession where I thought I could be happy working for the rest of my life.

I’m now a partner emeritus, which means I’m retiring soon, but I don’t think I’ll ever give up being part of the landscape architecture profession and advocating for it. I met Doris when she was OALA president, and I was chair of the practice legislation committee at the association. And I’m also currently the president of the Landscape Architecture Canada Foundation, which is the foundation that provides grants for research and scholarships to students.

Shelley Long: In my high school years, I was quite the environmental activist: started a green club at my high school (secured lots of funding for it) and participated in eco art contests. [After graduating from U of T], I worked for five years in Vancouver in both private practice and as adjunct professor at the University of British Columbia, which I found a very rewarding experience.

Four years ago, I moved to Rotterdam in the Netherlands, to join the team at West 8 Urban Design and Landscape Architecture. I had read [founder] Adriaan Geuze’s book when I was a student in Vancouver and actually attended his lecture when I was studying at the Daniels Faculty. I really wanted to work with him, so I guess I made that dream come true.

These days, protecting natural systems is a paramount aspect of designing landscapes. How does this intersect with your work?

Long: As landscape architects, our role is to help connect people with natural systems. I chose landscape architecture because it dealt with open systems and not closed ones. Landscapes only become better with time, whereas buildings start to fall apart the moment they’re complete. I thought, instead of making a fixed-point contribution, why not make something that gets better and more beautiful with time.

Whatever landscape architects do, there’s a ripple effect, a downstream effect that becomes exponential.

Naylor: I agree with Shelley. To stay in this profession, you have to be able to embrace and articulate the larger vision of what it does. There have been environmental catastrophes, including climate change, that have made taking care of the physical environment and natural systems more understandable and urgent, whether they’re urban systems that provide natural environments or larger ecosystems.

Chee: These issues, as Eha said, have come to the fore because of events that are happening now. But that’s how we’ve always projected our work: adapting to climate change, being more sustainable, being more diverse in our work. And whatever we do, small or big, there’s a ripple effect, a downstream effect that becomes exponential.

Has there been a paradigm shift within the profession when it comes to addressing these issues?

Naylor: Absolutely. In the 1980s, the concept of large-scale ecological restoration just wasn’t accepted. For example, I think it was probably in the early eighties that Michael Hough developed the strategy for the Lower Don Lands, and it involved recreating wetlands. He worked with a geomorphologist. And that idea, I think, was initially outlandish for many and now it is mainstream thinking. But it’s probably taken 25 or 30 years for it to be accepted.

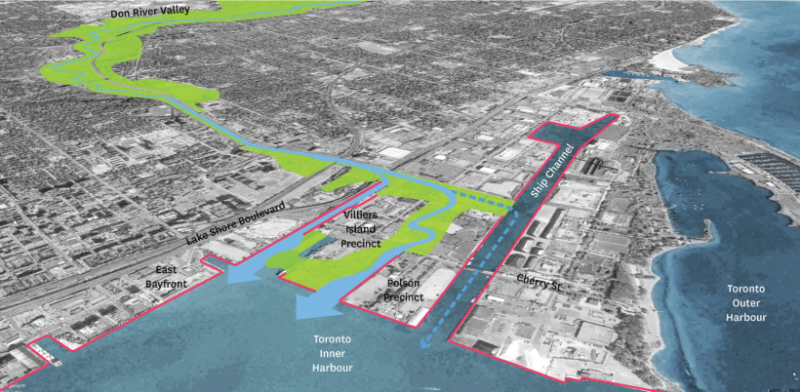

Chee: What they’re doing now in the Port Lands is ecology-based. And I go back to thinking about how it has shifted. Well, let’s look at trees, for instance. In the early days, we were choosing trees to plant for their aesthetics, not so much their ecological effects. Now, we’re planting for sustainability, for carbon capture.

Long: By the time I came into the profession, a lot of the paradigm shifts were already in place, which is a good thing, I guess, in how this way of thinking has become ingrained in the profession. But I could speculate that it might also be a bad thing. We sometimes put a lot of pressure on ourselves as young professionals to say that landscape architecture is going to save the world. I need to be realistic about that. We need to work together across disciplines and backgrounds to solve climate change, and also convey that landscape architects can’t and shouldn’t go at this alone.

Can you cite some of the projects that have addressed climage issues through landscape architecture?

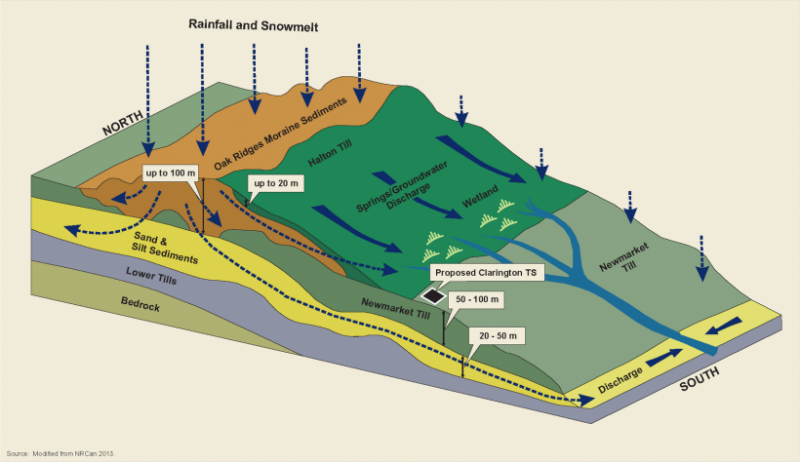

Chee: One project we just finished is the Clarington TS Project. Eha’s company, Dillon, has helped us with it. This is a major centre that transmits 500-kilovolt power to the eastern borders of Northern Ontario. It just so happened that this piece of land sits on moraine, has two streams running through, a little woodlot, and most of it was cultivated for agriculture.

Due to the number of towers that had to go into this project, as well as the station itself, we couldn’t allow the farmers to come back and use that land. We looked at the various ecosystems, and the different methods to enhance the natural system. We worked with the local conservation authority, which helped us greatly in finding the right methodologies to incorporate into this piece of property. And the last thing that we did was create a small wetland to help ease up on some of the runoffs that was happening downstream.

Long: In the Netherlands, there’s a project I’m involved with called the Noordward polder, where the Dutch government decided that the river needed more room to allow it to flood because of the extreme events that are happening more frequently. As part of it, all of the farmers [on an old historic polder] were to be moved away, in order to transform it into an ecological park.

West 8 was the sub-consultant on this project and had this idea of: how about we raise the inundation dikes, raise all the lands that the farmers are on? They go away for a few years, we rebuild their houses on higher ground, and they then live within the changing landscape.

And now what you see is that the farmers are able to stay in their homes, and you have a new type of place created, [a paragon of] what we call flood tourism. People actually go there and can see when everything is flooded except for the little rows, the little farmhouses, and the little pump stations. People, I think, are craving that. They want to understand how the landscape works, in relation to extreme events and climate change.

Naylor: One of the projects that I spent a lot of time working on was the Windsor-Essex Parkway [now called the Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway] which is the extension of the 401 Highway right through the city of Windsor, Ontario.

We took the results of multiple environmental assessments conducted over the years and developed a design strategy, which essentially put the highway into a trench. We created 11 land bridges across the trench. There was, I believe, almost 100 hectares of ecological restoration of tallgrass prairie and oak savanna.

It was an incredible project, because it took what would normally be and what the community thought would be a blight and turned it into an incredible ecological resource. We also had the privilege of working the local Indigenous community, the Walpole Island First Nation, and we were able to express both their culture and the project through art and signage.